Scroll down for today's Writing Wednesday assignment.

Citing Evidence: Can Lying Ever Be Kind?

Write two (2) paragraphs (5 sentences each) using evidence from the above video, and textual evidence from the transcript under the assignment.

Paragraph 1:

Describe why good or kind people tell lies. Are they trying to gain something for themselves, or is something else happening here? How can a small dose of untruth make sure that a big truth remains safe? Why do kind people only ever lie when there is almost no chance of their untruths being detected? Give an example of when you yourself might tell a kind lie to a member of your family. Why would a lie be better than the truth in this situation? End your first paragraph with a summary of the video and transcript's main argument.

Paragraph 2:

Begin your second paragraph with a statement of whether or not you agree with the video and transcript's main argument. Discuss the example of the woman who goes away to a conference (from the video and the transcript below). How is her lie and example of being kind? How would things have turned out much worse if she had told the truth. Here, explain what you would have done in her situation. Do you agree that telling the truth here would lead to much worse outcomes, or much better outcomes? If you were the person who stayed home in this situation, would you want the absolute truth, or would you rather have the untrue version? Explain your position on the matter. In summary, how can telling a lie be a kinder, gentler option?

Transcript of video:

Why Kind People Always Lie

Truly good people are always ready and even, at times, highly enthusiastic about telling lies. This sounds odd only because we are in the grip of a heroic but indiscriminate and delusional addiction to truth-telling.

|

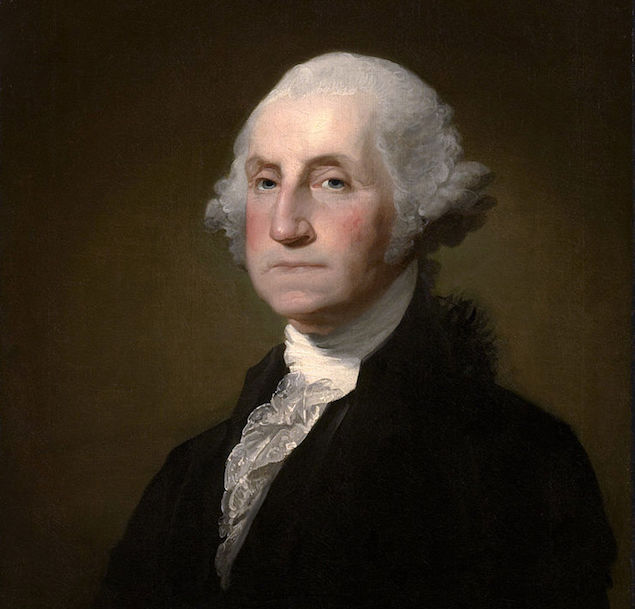

A lot of it can be blamed on George Washington, first president of the United States. Legend recounts how, at the age of six, he was given a little axe as a present. He was so excited with the gift that he went straight into the garden and hacked down a beautiful cherry tree. His father was furious when he discovered the chopped tree and asked George if he was responsible. The boy was said to have replied: ‘Father, I cannot tell a lie. It was I.’ The story is probably apocryphal, but it has stuck because it encapsulates an ideal to which we are intensely collectively committed: a devotion to the truth in spite of the cost it exacts on oneself. In this scenario, the liar is odious because they seek to evade a necessary and important truth for the sake of low personal gain. |

But good people do not lie for their own benefit. They aren’t protecting themselves and they aren’t disloyal to the facts out of mendacity: they tell lies because (paradoxical as it sounds at first) they love the truth intensely and out of good-will for the person they are deceiving.

|

We’re ready enough to admit to a role for lies in certain situations. You might be visiting an elderly aunt who prides herself on her talent for carrot cakes with vanilla icing. But her heyday is long gone. Now she muddles up the recipe and sometimes forgets how long the butter has been in the fridge. The result is pretty off-putting. But it’s deeply important for her to feel that she’s still able to please others. That’s why you lie.

The lie isn’t produced to protect oneself. It is told out of loyalty to a bigger truth – that one loves the aunt – that would be threatened by full disclosure. As is so often the case, a great truth has to pass into the mind of another person via a smaller falsehood. |

What makes falsehoods so necessary is our proclivity for making unfortunate associations. It is, in theory, of course entirely possible to love someone deeply and at the same time believe they are terrible at baking. But in our own minds, the rejection of our cakes tends to feel synonymous with the rejection of our being. We’re forcing any half decent person to lie to us – by the obtuseness of our thought-processes. It is because the aunt is in the grip of a falsehood (‘if you don’t like my cake, you can’t like me’) that we will have to offer her a dose of untruth (‘I like your cake’) by which we can make sure that a big truth (‘I like you’) remains safe.

The same principle applies in more tricky situations. Suppose a woman goes away to a conference. One night, after a lovely conversation in the bar, she gets carried away and slips into bed with an international colleague. They don’t make love but have a sweet time. They rub their lips together and entwine their legs. They will almost certainly never see one another again, it wasn’t an attempt to start a long-term relationship and it meant very little. When the woman gets home, her partner asks how her evening was. She says she watched CNN and ordered a club sandwich in her room on her own.

She lies because she knows her partner well and can predict how he would respond to the truth. He would be wounded to the core, would be convinced that his wife didn’t love him and would probably conclude that divorce was the only option.

But this assessment of the truth would not be true. In reality, it is of course eminently possible to love someone deeply and every so often go to bed with another person. And yet, kind people understand the entrenched and socially-endorsed associations between infidelity and callousness. For almost all of us, the news ‘I spent a night with a colleague from the Singapore office’ (which is true) has to end up meaning ‘I don’t love you anymore’ (which is not true at all). And so we have to say ‘I didn’t sleep with anyone’ (which is untrue) in the name of securing the greater idea: ‘I still love you’ (which is overwhelmingly true).

The same principle applies in more tricky situations. Suppose a woman goes away to a conference. One night, after a lovely conversation in the bar, she gets carried away and slips into bed with an international colleague. They don’t make love but have a sweet time. They rub their lips together and entwine their legs. They will almost certainly never see one another again, it wasn’t an attempt to start a long-term relationship and it meant very little. When the woman gets home, her partner asks how her evening was. She says she watched CNN and ordered a club sandwich in her room on her own.

She lies because she knows her partner well and can predict how he would respond to the truth. He would be wounded to the core, would be convinced that his wife didn’t love him and would probably conclude that divorce was the only option.

But this assessment of the truth would not be true. In reality, it is of course eminently possible to love someone deeply and every so often go to bed with another person. And yet, kind people understand the entrenched and socially-endorsed associations between infidelity and callousness. For almost all of us, the news ‘I spent a night with a colleague from the Singapore office’ (which is true) has to end up meaning ‘I don’t love you anymore’ (which is not true at all). And so we have to say ‘I didn’t sleep with anyone’ (which is untrue) in the name of securing the greater idea: ‘I still love you’ (which is overwhelmingly true).

|

However much they love the truth, good people have an even greater commitment to something else: being kind towards others. They grasp (and make allowances for) the ease with which a truth can produce desperately unhelpful convictions in the minds of others and are therefore not proudly over-committed to accuracy at every turn. Their loyalty is reserved for something they take to be far more important than literal narration: the sanity and well-being of their audiences. Telling the truth, they understand, isn’t a matter of the sentence by sentence veracity of one’s words, it’s a matter of ensuring that, after one has spoken, the other person can be left with a true picture of reality.

|

This concern for the well-being of others explains why kind people only ever lie when there is little chance of their untruths being detected. They know that a lie which gets unearthed will cause proper and unjustifiable trouble, leading the other person to a second and even more radically false conclusion: not only that ‘you don’t love me’ (first untruth) but also that ‘you lied to me because you don’t love me’ (a second, even greater untruth).

It can feel condescending to hear the logic of the good liar spelled out. But that’s only because we don’t like to acknowledge the fragility of our own minds. We may believe we’re heroically ready to embrace the truth, however painful. We may insist that others should tell us everything, whatever they do. But we thereby discount our own powerful tendencies to emotional indigestion. It’s why we should not only occasionally tell untruths – but actively hope that, from time to time, others will lie to us – and quietly hope that we will never find out that they have.

It can feel condescending to hear the logic of the good liar spelled out. But that’s only because we don’t like to acknowledge the fragility of our own minds. We may believe we’re heroically ready to embrace the truth, however painful. We may insist that others should tell us everything, whatever they do. But we thereby discount our own powerful tendencies to emotional indigestion. It’s why we should not only occasionally tell untruths – but actively hope that, from time to time, others will lie to us – and quietly hope that we will never find out that they have.