Dr. H. A. Moynihan, by Lucia Berlin

I hated my Catholic school. Terrified by the nuns, I struck Sister Cecilia one hot Texas day and was expelled. It was only a misunderstanding, but I was expelled anyway. As punishment, I had to work every day of summer vacation in Grandpa’s dental office. I knew the real reason was my mother and Grandpa didn’t want me to play with the neighborhood children.

I’m sure they also wanted to spare me Mamie’s dying, her moaning, her friends’ praying, the stench and the flies. At night, with the help of morphine, she would doze off and my mother and Grandpa would each drink alone in their separate rooms. I could hear the separate gurgles of bourbon from the porch where I slept.

Everybody hated Grandpa but Mamie, and me, I guess. Every night he got drunk and mean. He was cruel and bigoted and proud. He had shot my uncle John’s eye out during a quarrel and had shamed and humiliated my mother all her life. She wouldn’t speak to him, wouldn’t even get near him because he was so filthy, slopping food and spitting, leaving wet cigarettes everywhere. Plaster from teeth molds covered him with white specks, like he was a painter or a statue.

He was the best dentist in West Texas, maybe in all of Texas. Many people said so, and I believed it. It wasn’t true that his patients were all old winos or Mamie’s friends, my mother said that. Distinguished men came even from Dallas or Houston because he made such wonderful false teeth. His false teeth never slipped or whistled, and they looked completely real. He had invented a secret formula to color them right, sometimes even made them chipped or yellowed, with fillings and caps on them.

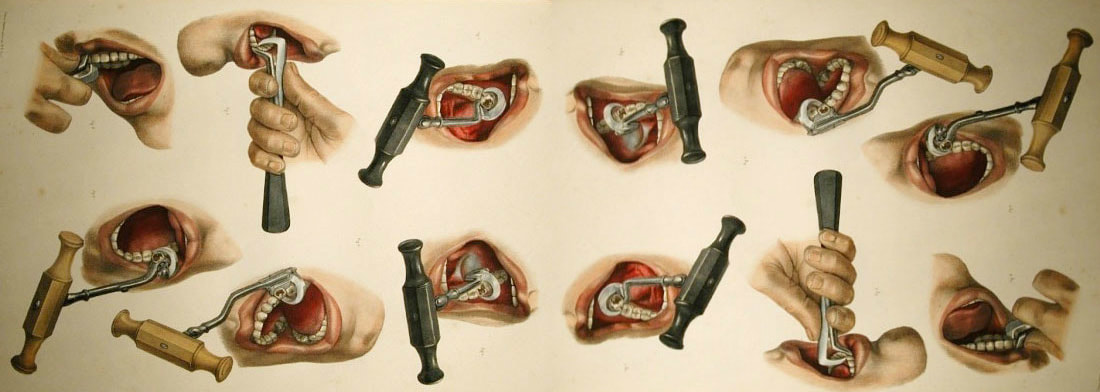

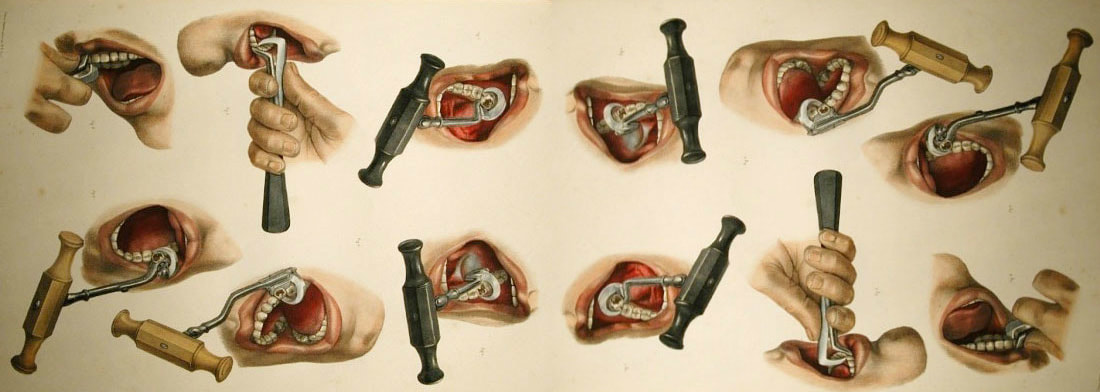

Grandpa barely spoke to me all summer. I sterilized and laid out his instruments, tied towels around the patients’ necks, held the Stom Aseptine mouthwash cup and told them to spit. When there weren’t any patients, he went into his workshop to make teeth.

He wouldn’t let anyone in his workshop. It hadn’t been cleaned in forty years. I went in when he went to the bathroom. The windows were caked black with dirt and plaster and wax. The only light came from two flickering blue Bunsen burners. Huge sacks of plaster stacked against the walls, sifted over onto a floor lumpy with chunks of broken tooth molds, and jars of various single teeth.

There was no door between the room where he worked on patients and the waiting room. While he worked, he would turn around to talk to people in the waiting room, waving his drill. The extraction patients would recover on a chaise longue; the rest sat on windowsills or radiators.

There weren’t any magazines. If someone brought one and left it there, Grandpa would throw it away. He just did this to be contrary, my mother said. He said it was because it drove him crazy, people sitting there turning the pages.

When his patients weren’t sitting, they wandered around the room fooling with things on the two safes. Buddhas, skulls with false teeth wired to open and close, snakes that bit you if you pulled their tails, domes you turned over and it snowed. On the ceiling was a sign, WHAT THE HELL YOU LOOKING UP HERE FOR? The safes contained gold and silver for fillings, stacks of money, and bottles of Jack Daniel’s.

When people called for appointments, Grandpa had me tell them he was no longer taking patients, so as summer went on, there was less and less to do. Finally, just before Mamie died, there were no patients at all. Grandpa just stayed locked in his workshop or office. I used to go up on the roof sometimes. You could see Juárez and all of downtown El Paso from there. I would pick out one person in the crowd and follow him with my eyes until he disappeared. But mostly I just sat inside on the radiator, looking down at Yandell Drive. I spent hours decoding letters from Captain Marvel Pen Pals, although that was really boring; the code was just A for Z, B for Y, etc.

Nights were long and hot. Mamie’s friends stayed even when she slept, reading from the Bible, singing sometimes. Grandpa went out, to the Elks, or to Juárez. The 8-5 cabdriver helped him up the stairs. My mother went out to play bridge, she said, but she came home drunk, too. The Mexican kids played outside until very late. I watched the girls from the porch. They played jacks, squatting on the concrete under the streetlight. I ached to play with them. The sound of the jacks was magical to me, the toss of the jacks like brushes on a drum or like rain, when a gust of wind shimmers it against the windowpane.

One morning when it was still dark, Grandpa woke me up. It was Sunday. I dressed while he called the cab. To call a cab he asked the operator for 8-5 and when they answered, he said, “How about a little transportation?” He didn’t answer when the cabdriver asked why we were going to the office on Sunday. It was dark and scary in the lobby. Cockroaches clattered across the tiles and magazines grinned at us behind bars of grating. He drove the elevator, maniacally crashing up and then down and up again until we finally stopped above the fifth floor and jumped down. It was very quiet after we stopped. All you heard were church bells and the Juárez trolley.

At first I was too frightened to follow him into the workshop, but he pulled me in. It was dark, like in a movie theater. He lit the gasping Bunsen burners. I still couldn’t see, couldn’t see what he wanted me to. He took a set of false teeth down from a shelf and moved them close to the flame on the marble block. I shook my head.

“Keep lookin’ at them.” Grandpa opened his mouth wide and I looked back and forth between his own teeth and the false ones.

“They’re yours!” I said.

The false teeth were a perfect replica of the teeth in Grandpa’s mouth, even the gums were an ugly, sick pale pink. The teeth were filled and cracked, some were chipped or worn away. He had changed only one tooth, one in front that he had put a gold cap on. That’s what made it a work of art, he said.

“How did you get all those colors?”

“Pretty dang good, eh? Well … is it my masterpiece?”

“Yes.” I shook his hand. I was very happy to be there.

“How do you fit them?” I asked. “Will they fit?”

Usually he pulled out all the teeth, let the gums heal, then made an impression of the bare gum.

“Some of the new guys are doing it this way. You take the impression before you pull the teeth, make the dentures and put them in before the gums have a chance to shrink.”

“When are you getting your teeth pulled?”

“Right now. We’re going to do it. Go get things ready.”

I plugged in the rusty sterilizer. The cord was frayed; it sparked. He started toward it. “Never mind the—” but I stopped him. “No. They have to be sterile,” and he laughed. He put his whiskey bottle and cigarettes on the tray, lit a cigarette, and poured a paper cup full of Jack Daniel’s. He sat down in the chair. I fixed the reflector, tied a bib on him, and pumped the chair up and back.

“Boy, I’ll bet a lot of your patients would like to be in my shoes.”

“That thing boiling yet?”

“No.” I filled some paper cups with Stom Aseptine and got out a jar of smelling salts.

“What if you pass out?” I asked.

“Good. Then you can pull them. Grab them as close as you can, twist and pull at the same time. Gimme a drink.”

I handed him a cup of Stom Aseptine. “Wise guy.” I poured him whiskey.

“None of your patients get a drink.”

“They’re my patients, not yours.”

“Okay, it’s boiling.” I drained the sterilizer into the spitting bowl, laid out a towel. Using another one, I placed the instruments in an arc on the tray above his chest.

“Hold the little mirror for me,” he said and took the pliers.

I stood on the footrest between his knees, to hold the mirror close. The first three teeth came out easy. He handed them to me and I tossed them into the barrel by the wall. The incisors were harder, one in particular. He gagged and stopped, the root still stuck in his gum. He made a funny noise and shoved the pliers into my hand. “Take it!” I pulled at it. “Scissors, you fool!” I sat down on the metal plate between his feet. “Just a minute, Grandpa.”

He reached over above me for the bottle, drank, then took a different tool from the tray. He began to pull the rest of his bottom teeth without a mirror. The sound was the sound of roots being ripped out, like trees being torn from winter ground. Blood dripped onto the tray, plop, plop, onto the metal where I sat.

He started laughing so hard I thought he had gone mad. He fell over on top of me. Frightened, I leaped up so hard I pushed him back into the tilted chair. “Pull them!” he gasped. I was afraid, wondered quickly if it would be murder if I pulled them and he died.

“Pull them!” He spat a thin red waterfall down his chin.

I pumped the chair way back. He was limp, did not seem to feel me twist the back top teeth sideways and out. He fainted, his lips closing like gray clamshells. I opened his mouth and shoved a paper towel into one side so I could get the three back teeth that remained.

The teeth were all out. I tried to bring the chair down with the foot pedal, but hit the wrong lever, spinning him around, spattering circles of blood on the floor. I left him, the chair creaking slowly to a stop. I wanted some tea bags, he had people bite down on them to stop the bleeding. I dumped Mamie’s drawers out: talcum, prayer cards, thank you for the flowers. The tea bags were in a canister behind the hot plate.

The towel in his mouth was soaked crimson now. I dropped it on the floor, shoved a handful of tea bags into his mouth and held his jaws closed. I screamed. Without any teeth, his face was like a skull, white bones above the vivid bloody throat. Scary monster, a teapot come alive, yellow and black Lipton tags dangling like parade decorations. I ran to phone my mother. No nickel. I couldn’t move him to get to his pockets. He had wet his pants; urine dripped onto the floor. A bubble of blood kept appearing and bursting in his nostril.

The phone rang. It was my mother. She was crying. The pot roast, a nice Sunday dinner. Even cucumbers and onions, just like Mamie. “Help! Grandpa!” I said and hung up.

He had vomited. Oh good, I thought, and then giggled because it was a silly thing to think oh good about. I dropped the tea bags into the mess on the floor, wet some towels and washed his face. I opened the smelling salts under his nose, smelled them myself, shuddered.

“My teeth!” he yelled.

“They’re gone!” I called, like to a child. “All gone!”

“The new ones, fool!”

I went to get them. I knew them now, they were exactly like his mouth had been inside.

He reached for them, like a Juárez beggar, but his hands shook too badly.

“I’ll put them in. Rinse first.” I handed him the mouthwash. He rinsed and spat without lifting his head. I poured peroxide over the teeth and put them in his mouth. “Hey, look!” I held up Mamie’s ivory mirror.

“Well, dad gum!” He was laughing.

“A masterpiece, Grandpa!” I laughed too, kissed his sweaty head.

“Oh my God.” My mother shrieked, came toward me with her arms outstretched. She slipped in the blood, and slid into the teeth barrels. She held on to get her balance.

“Look at his teeth, Mama.”

She didn’t even notice. Couldn’t tell the difference. He poured her some Jack Daniel’s. She took it, toasted him distractedly, and drank.

“You’re crazy, Daddy. He’s crazy. Where did all the tea bags come from?”

His shirt made a tearing sound coming unstuck from his skin. I helped him wash his chest and wrinkled belly. I washed myself, too, and put on a coral sweater of Mamie’s. The two of them drank, silent, while we waited for the 8-5 cab. I drove the elevator down, landed it pretty close to the bottom. When we got home, the driver helped Grandpa up the stairs. He stopped at Mamie’s door, but she was asleep.

In bed, Grandpa slept too, his teeth bared in a Bela Lugosi grin. They must have hurt.

“He did a good job,” my mother said.

“You don’t still hate him, do you Mama?”

“Oh, yes,” she said. “Yes I do.”

I’m sure they also wanted to spare me Mamie’s dying, her moaning, her friends’ praying, the stench and the flies. At night, with the help of morphine, she would doze off and my mother and Grandpa would each drink alone in their separate rooms. I could hear the separate gurgles of bourbon from the porch where I slept.

Everybody hated Grandpa but Mamie, and me, I guess. Every night he got drunk and mean. He was cruel and bigoted and proud. He had shot my uncle John’s eye out during a quarrel and had shamed and humiliated my mother all her life. She wouldn’t speak to him, wouldn’t even get near him because he was so filthy, slopping food and spitting, leaving wet cigarettes everywhere. Plaster from teeth molds covered him with white specks, like he was a painter or a statue.

He was the best dentist in West Texas, maybe in all of Texas. Many people said so, and I believed it. It wasn’t true that his patients were all old winos or Mamie’s friends, my mother said that. Distinguished men came even from Dallas or Houston because he made such wonderful false teeth. His false teeth never slipped or whistled, and they looked completely real. He had invented a secret formula to color them right, sometimes even made them chipped or yellowed, with fillings and caps on them.

Grandpa barely spoke to me all summer. I sterilized and laid out his instruments, tied towels around the patients’ necks, held the Stom Aseptine mouthwash cup and told them to spit. When there weren’t any patients, he went into his workshop to make teeth.

He wouldn’t let anyone in his workshop. It hadn’t been cleaned in forty years. I went in when he went to the bathroom. The windows were caked black with dirt and plaster and wax. The only light came from two flickering blue Bunsen burners. Huge sacks of plaster stacked against the walls, sifted over onto a floor lumpy with chunks of broken tooth molds, and jars of various single teeth.

There was no door between the room where he worked on patients and the waiting room. While he worked, he would turn around to talk to people in the waiting room, waving his drill. The extraction patients would recover on a chaise longue; the rest sat on windowsills or radiators.

There weren’t any magazines. If someone brought one and left it there, Grandpa would throw it away. He just did this to be contrary, my mother said. He said it was because it drove him crazy, people sitting there turning the pages.

When his patients weren’t sitting, they wandered around the room fooling with things on the two safes. Buddhas, skulls with false teeth wired to open and close, snakes that bit you if you pulled their tails, domes you turned over and it snowed. On the ceiling was a sign, WHAT THE HELL YOU LOOKING UP HERE FOR? The safes contained gold and silver for fillings, stacks of money, and bottles of Jack Daniel’s.

When people called for appointments, Grandpa had me tell them he was no longer taking patients, so as summer went on, there was less and less to do. Finally, just before Mamie died, there were no patients at all. Grandpa just stayed locked in his workshop or office. I used to go up on the roof sometimes. You could see Juárez and all of downtown El Paso from there. I would pick out one person in the crowd and follow him with my eyes until he disappeared. But mostly I just sat inside on the radiator, looking down at Yandell Drive. I spent hours decoding letters from Captain Marvel Pen Pals, although that was really boring; the code was just A for Z, B for Y, etc.

Nights were long and hot. Mamie’s friends stayed even when she slept, reading from the Bible, singing sometimes. Grandpa went out, to the Elks, or to Juárez. The 8-5 cabdriver helped him up the stairs. My mother went out to play bridge, she said, but she came home drunk, too. The Mexican kids played outside until very late. I watched the girls from the porch. They played jacks, squatting on the concrete under the streetlight. I ached to play with them. The sound of the jacks was magical to me, the toss of the jacks like brushes on a drum or like rain, when a gust of wind shimmers it against the windowpane.

One morning when it was still dark, Grandpa woke me up. It was Sunday. I dressed while he called the cab. To call a cab he asked the operator for 8-5 and when they answered, he said, “How about a little transportation?” He didn’t answer when the cabdriver asked why we were going to the office on Sunday. It was dark and scary in the lobby. Cockroaches clattered across the tiles and magazines grinned at us behind bars of grating. He drove the elevator, maniacally crashing up and then down and up again until we finally stopped above the fifth floor and jumped down. It was very quiet after we stopped. All you heard were church bells and the Juárez trolley.

At first I was too frightened to follow him into the workshop, but he pulled me in. It was dark, like in a movie theater. He lit the gasping Bunsen burners. I still couldn’t see, couldn’t see what he wanted me to. He took a set of false teeth down from a shelf and moved them close to the flame on the marble block. I shook my head.

“Keep lookin’ at them.” Grandpa opened his mouth wide and I looked back and forth between his own teeth and the false ones.

“They’re yours!” I said.

The false teeth were a perfect replica of the teeth in Grandpa’s mouth, even the gums were an ugly, sick pale pink. The teeth were filled and cracked, some were chipped or worn away. He had changed only one tooth, one in front that he had put a gold cap on. That’s what made it a work of art, he said.

“How did you get all those colors?”

“Pretty dang good, eh? Well … is it my masterpiece?”

“Yes.” I shook his hand. I was very happy to be there.

“How do you fit them?” I asked. “Will they fit?”

Usually he pulled out all the teeth, let the gums heal, then made an impression of the bare gum.

“Some of the new guys are doing it this way. You take the impression before you pull the teeth, make the dentures and put them in before the gums have a chance to shrink.”

“When are you getting your teeth pulled?”

“Right now. We’re going to do it. Go get things ready.”

I plugged in the rusty sterilizer. The cord was frayed; it sparked. He started toward it. “Never mind the—” but I stopped him. “No. They have to be sterile,” and he laughed. He put his whiskey bottle and cigarettes on the tray, lit a cigarette, and poured a paper cup full of Jack Daniel’s. He sat down in the chair. I fixed the reflector, tied a bib on him, and pumped the chair up and back.

“Boy, I’ll bet a lot of your patients would like to be in my shoes.”

“That thing boiling yet?”

“No.” I filled some paper cups with Stom Aseptine and got out a jar of smelling salts.

“What if you pass out?” I asked.

“Good. Then you can pull them. Grab them as close as you can, twist and pull at the same time. Gimme a drink.”

I handed him a cup of Stom Aseptine. “Wise guy.” I poured him whiskey.

“None of your patients get a drink.”

“They’re my patients, not yours.”

“Okay, it’s boiling.” I drained the sterilizer into the spitting bowl, laid out a towel. Using another one, I placed the instruments in an arc on the tray above his chest.

“Hold the little mirror for me,” he said and took the pliers.

I stood on the footrest between his knees, to hold the mirror close. The first three teeth came out easy. He handed them to me and I tossed them into the barrel by the wall. The incisors were harder, one in particular. He gagged and stopped, the root still stuck in his gum. He made a funny noise and shoved the pliers into my hand. “Take it!” I pulled at it. “Scissors, you fool!” I sat down on the metal plate between his feet. “Just a minute, Grandpa.”

He reached over above me for the bottle, drank, then took a different tool from the tray. He began to pull the rest of his bottom teeth without a mirror. The sound was the sound of roots being ripped out, like trees being torn from winter ground. Blood dripped onto the tray, plop, plop, onto the metal where I sat.

He started laughing so hard I thought he had gone mad. He fell over on top of me. Frightened, I leaped up so hard I pushed him back into the tilted chair. “Pull them!” he gasped. I was afraid, wondered quickly if it would be murder if I pulled them and he died.

“Pull them!” He spat a thin red waterfall down his chin.

I pumped the chair way back. He was limp, did not seem to feel me twist the back top teeth sideways and out. He fainted, his lips closing like gray clamshells. I opened his mouth and shoved a paper towel into one side so I could get the three back teeth that remained.

The teeth were all out. I tried to bring the chair down with the foot pedal, but hit the wrong lever, spinning him around, spattering circles of blood on the floor. I left him, the chair creaking slowly to a stop. I wanted some tea bags, he had people bite down on them to stop the bleeding. I dumped Mamie’s drawers out: talcum, prayer cards, thank you for the flowers. The tea bags were in a canister behind the hot plate.

The towel in his mouth was soaked crimson now. I dropped it on the floor, shoved a handful of tea bags into his mouth and held his jaws closed. I screamed. Without any teeth, his face was like a skull, white bones above the vivid bloody throat. Scary monster, a teapot come alive, yellow and black Lipton tags dangling like parade decorations. I ran to phone my mother. No nickel. I couldn’t move him to get to his pockets. He had wet his pants; urine dripped onto the floor. A bubble of blood kept appearing and bursting in his nostril.

The phone rang. It was my mother. She was crying. The pot roast, a nice Sunday dinner. Even cucumbers and onions, just like Mamie. “Help! Grandpa!” I said and hung up.

He had vomited. Oh good, I thought, and then giggled because it was a silly thing to think oh good about. I dropped the tea bags into the mess on the floor, wet some towels and washed his face. I opened the smelling salts under his nose, smelled them myself, shuddered.

“My teeth!” he yelled.

“They’re gone!” I called, like to a child. “All gone!”

“The new ones, fool!”

I went to get them. I knew them now, they were exactly like his mouth had been inside.

He reached for them, like a Juárez beggar, but his hands shook too badly.

“I’ll put them in. Rinse first.” I handed him the mouthwash. He rinsed and spat without lifting his head. I poured peroxide over the teeth and put them in his mouth. “Hey, look!” I held up Mamie’s ivory mirror.

“Well, dad gum!” He was laughing.

“A masterpiece, Grandpa!” I laughed too, kissed his sweaty head.

“Oh my God.” My mother shrieked, came toward me with her arms outstretched. She slipped in the blood, and slid into the teeth barrels. She held on to get her balance.

“Look at his teeth, Mama.”

She didn’t even notice. Couldn’t tell the difference. He poured her some Jack Daniel’s. She took it, toasted him distractedly, and drank.

“You’re crazy, Daddy. He’s crazy. Where did all the tea bags come from?”

His shirt made a tearing sound coming unstuck from his skin. I helped him wash his chest and wrinkled belly. I washed myself, too, and put on a coral sweater of Mamie’s. The two of them drank, silent, while we waited for the 8-5 cab. I drove the elevator down, landed it pretty close to the bottom. When we got home, the driver helped Grandpa up the stairs. He stopped at Mamie’s door, but she was asleep.

In bed, Grandpa slept too, his teeth bared in a Bela Lugosi grin. They must have hurt.

“He did a good job,” my mother said.

“You don’t still hate him, do you Mama?”

“Oh, yes,” she said. “Yes I do.”